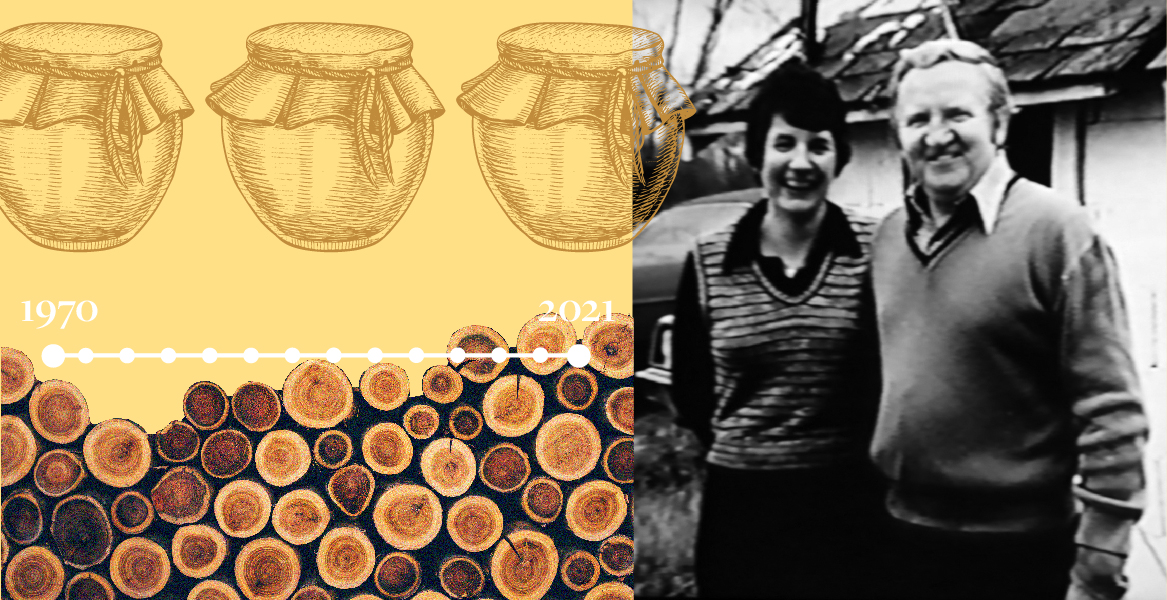

Long before Norm and Rosemary Byrne established a multi-million dollar company that specializes in sophisticated electrical products, their lives were measured in cords of wood and quarts of jam.

And as the couple prepares to celebrate the company’s 50th year in business throughout 2021, they continue to embrace touchstones like pluck, hard work, faith – and stubbornness – maintaining that in our present-day world of flux, old-time values still matter and still work.

“Norm’s degree came from the school of experience,” says Tom Hiller, who served as long-time financial adviser for Byrne Electrical Specialists, Inc., and has known founder Norm Byrne for more than 30 years. “He never went to college and he came from humble beginnings, but through dogged determination, he’s ushered the company through recessions, upturns, downturns and more. And that’s benefited not only its employees, but a whole larger community.”

It would be difficult for most of Byrne’s hundreds of employees to even imagine it, but both Norm and Rosemary grew up without indoor plumbing, attended one-room schoolhouses, hunted and harvested most their own food, and relied on bedrock faith to intercede in times of need. Both were raised by parents who squeezed a living from farms and often knew what it was to go without.

From those hardscrabble origins, Norm and Rosemary transformed Byrne from a crowded basement experiment in Ada into a global force, competing today on a fiercely competitive industrial stage from their headquarters in Rockford.

The primary moving force has been Norm, a 79-year-old paradox whose sometimes gruff exterior and insistence on doing things his way belies a sense of fairness and generosity that is storied, especially among long-time employees.

Norm’s management style is the stuff of legend, hardly what you’d find in today’s MBA manuals. “Ya gotta get ‘em movin’,” he says with a chuckle. Which would translate with Norm storming each morning into work -- thus the moniker “Stormin’ Norman” -- seeing or inventing a crisis, and dispatching orders all around. Then he’d leave for breakfast, returning to witness changes that another might have coaxed out with kid gloves.

Before there were even a handful of employees to roust, though, the jobs fell to Norm and Rosemary alone, who managed the rigors of self-employment along with the challenges that come with paying a mortgage, reconciling loans and raising children.

Product development in those early days? Rosemary’s turn to chuckle: “He used to come home with some part that he’d carry around with him, clicking and clacking it, trying to make it work. He’d even bring it to bed with him, and all of a sudden I’d wake up because now I’m sleeping on the part.”

Early on, they were confronted by more than just long hours: Legendary is the would-be business partner who flimflammed $1,000 from the Byrnes just as they were getting started. Rather than prosecute, Norm and Rosemary negotiated a deal allowing him to pay back what he stole at the rate of $10 a month. It was only one of several challenging work experiences that would have prompted another couple to throw in the towel. It only steeled Norm’s resolve: “Starting over was never an option. There was nothing we couldn’t get through.”

Norm was born on New Year’s Eve 1940, the lone boy among seven sisters, one of whom would become a nun. He attended school a quarter-mile from the family farm on Honey Creek Road NE, a winding and picturesque stretch linking Ada and Cannonsburg in northern Kent County.

“It was a smaller farm; we sold milk and had some cash crops in wheat and beans. A few chickens and some pigs. We got electricity when I was may be 5 or 6 years old. In the beginning, there was a Delco system to run a couple of lights in the house and barn. Later, it ran a well pump, but only when my dad had money for gas. We got indoor plumbing when I was maybe 10.”

Norm graduated from Lowell High School in 1960, where he ran track, though his prep years were marked by tragedy when his dad died suddenly from a stroke in 1957. His school days were made even more difficult by dyslexia, a disorder involving difficulty with interpreting words, letters and symbols. Years later, he would transform that learning disability into a business asset, going on to become both an inventor and holder of multiple patents.

Some 80 miles northwest of Ada -- near New Era in Oceana County -- Rosemary was growing up similarly. She was born at the family homestead in January 1939 during a blizzard that marked one of the coldest winters then on record.

At the one-room schoolhouse Rosemary attended, there was no playground or equipment, so students would scrounge up a ball and invent games. The family resorted to an outhouse until Rosemary entered the fourth grade. Water was brought in to heat on a wood cookstove, and kerosene preceded electricity as a power source.

Throughout the rotating seasons, says Rosemary, the family canned “hundreds of quarts of everything – pears, peaches, beans, tomatoes, cherries, pickles and even our own sauerkraut.” For meat, her father and brothers hunted everything from deer to rabbits to squirrel to pheasant. “We also raised 100 chickens each year, which we always harvested in the fall, storing them in a freezer we rented over in Whitehall. We didn’t buy any groceries other than flour and sugar and salt and anything else we couldn’t grow or hunt or make.”

Following the eighth grade, Rosemary lived at and attended Mt. Mercy Academy in Grand Rapids, which then operated as a boarding school. Upon graduating in 1957, she entered St. Mary’s Hospital School of Nursing, becoming a registered nurse.

It’s while living in Grand Rapids during the summer of 1962 that Rosemary met Norm. After working the 3-11 p.m. shift as a nurse one night, she and her girlfriend drove to the now long-gone Dick’s Lakeside Inn on the south side of Big Crooked Lake near Grattan.

They were enjoying a beer and listening to music when Norm rolled in some time after midnight, after dropping off a gal he’d dated that evening. “He came up and asked me to dance and we talked a little, and then the place closed,” Rosemary recalls. “The next week, I went back, and he finally showed up and we danced again and talked and discovered that his sister and mine were both Sisters of Mercy and were in the convent together.

“He asked me for my phone number, and I was going to write it on a $10 bill he had, but then I told him ‘You’ll spend that before you ever call me’ so I found a piece of paper. He called me the following Wednesday, and we spent the day at Lake Michigan.”

Norm remembers it the same way, but with a twist. The day of their date, Norm relied on a buddy to finish a driveway he was pouring, but the friend fell short of what was expected. “I spent the next two days breaking out all the concrete and re-pouring it,” says Norm, “so that made for a pretty expensive date!”

They married in 1963 and started Byrne in a 12-by-12-foot room in the basement of their Ada home in 1970. During the installation of their first piece of heavy equipment – a wire cutter that weighed upwards of 500 pounds – it destroyed the bottom steps leading to the basement floor. They fixed the damage and never looked back.

Both worked other jobs while their fledgling business grew – Rosemary part-time as a nurse, and Norm at a variety of manufacturing positions, where he quickly discovered that he could absorb everything about a job to a point where he worked himself out of them.

“I never really had a job I hated, but not one I wanted to do all my life, either,” he says. Working for anybody else was my biggest problem.”

His big breaks came at the hands of two successful businessmen – Ed Mancewicz and Don Tjarksen. The latter convinced Norm to strike out on his own and sell his firm instrumentation for the marine industry. “I guess he saw something of the entrepreneurial spirit in me,” Norm remembers of Tjarksen.

Norm worked five years for Mancewicz at both Grand Rapids Spring & Wire and Grand Rapids Controls while the couple got their basement enterprise going. The two men bonded professionally and personally, and came to operate their respective businesses from the same industrial park in Rockford. Byrne moved to that location in 1979.

As Byrne grew, so too did the family, with Kelly, Kathy, Dan and Molly arriving in that order. In the beginning, the couple leaned on high-interest loans from sharks in Chicago because local banks wouldn’t provide them funds for operating capital. Norm never took a salary from the Byrne enterprise the first five years. Every supposed impasse only made him more relentless in his quest to succeed.

“There’s a saying we have at Byrne,” says Rosemary, and it’s ‘Don’t tell Norm no.’ He’ll only work harder to get through that wall.”

Norm bristles at the prospect of giving up or giving in: “The ones who survive are the ones who stick with it,” he says. “You’re going to have hard times.”

The secret, says Norm, is tied to lessons he and Rosemary both absorbed while adapting to tough times on their family farms, and one maxim in particular: “Don’t ever quit.”

Today, Byrne Electrical boasts well over $100 million in annual sales, relying on a workforce who churn out power and data distribution products for the home, healthcare and furniture industries not only from Rockford and nearby Lakeview, but in Mexico and China.